In 02006, I attended the SxSW conference in Austin, Texas where I heard James Surowiecki talking about the wisdom of crowds. I bought his book and have been hooked on the idea of prediction markets ever since.

In his book, he tells the story of Sir Francis Galton‘s folly into the world of group think. He was promoting eugenics which he believed intelligence and other skills where hereditary. This type of thinking puts experts in a more respected prominent position than the “non-educated masses”. In 01906, a livestock fair was the undoing of his theory and the start of something much bigger. At the fair an ox was on display and the contest was to guess the weight of the animal after it had been slaughtered and dressed. According to Galton, the people with the most experience in dealing with livestock would have the best chance of guessing correctly. We all probably would make the same logical error. The average person doesn’t know much about cattle and therefore their guesses are worthless. To prove himself right, he collected the nearly 800 submissions and statistically reviewed them all and this was a man who invented several statistical concepts! Not a single person guessed the correct weight of 1,198 pounds, but what came next is the astounding part. When every single guess was averaged together the mean value was 1,197 pounds, just one pound off! That was better than any single expert’s guess. This began the undoing of any sort of hereditary or job expertise. If you simply ask a diverse enough group of people, some people will guess too high, some too low, but overall they will average out to the best possible result—better than the experts.

There are plenty of criticisms of what is known as “the wisdom of crowds” one such came over 50 years prior to Galton, by Charles Mackay. In 01841, he wrote Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds attempting to convince us of the weakness of mankind and herd or group think. There is a PDF of the original book available for download.

Group think and the market place

If there is knowledge locked-up in everyone’s minds, there needs to be a consistent measurable way to analyze and manipulate it. Just as any one small fact isn’t useful on its own, there needs to be a mechanism to aggregate and weigh this knowledge. It turns out a market place is an ideal model.

Any data falls into one of three categories:

- Data that everyone knows about and gives you no competitive advantage

- Data that you need to know not because it gives you an advantage, but not knowing it can detrimental

- Data that only you have, and can (briefly) exploit

A prediction market can turn this third category of data to your advantage. Trading shares early before the data becomes common knowledge and trickles down into the first two categories allows for the highest reward. Previously, there was no advantage in “sharing” knowledge with others because there was no economic reward, you could be rewarded with Whuffie or street cred, but if it’s bad news you might not share at all. With a prediction market, it’s possible to capitalize on bad news, which brings problems to light faster and corrected before it lingers. It removes the elephant in the room.

A good market place has several specifics that you don’t find in a free market model. A prediction market needs a well-defined end date or closing criteria. This is important because everyone needs to assess the risks within a specified time period. A bad example would be “Is X company going to fold-up?” Given enough time every company eventually runs its course, even the oldest known company, Kongō Gumi after 1400 years of operation, was absorbed into another company. The question is 100% guaranteed to be true. It is more interesting to ask, “Is X company going to fold-up before the end of 02010?”. Now there is a defined end date to which risk vs. reward can be assessed. Without an end date no one would be willing to wager on the improbable event for a potentially high reward.

The next important criteria in a prediction market is that the series of shares are mutually exclusive and has only one definitive outcome. A bad example of shares would be a prediction market that asks “Why will Brian be late to the meeting?”

- Oversleeps

- Forgets to mark his calendar

- Misses the Bus

- Has the flu

There are two problems with this list. Firstly, there could be two possible outcomes. I could have the flu AND oversleep. Therefore, two shares would pay out, which isn’t a good scenario. Secondly, this list does not account for other possible outcomes such as; “Hit by a bus” or “Is out of town and misses returning flight” or any infinite number of others possibilities. The better question to ask is “Will Brian be late to the meeting?” Yes or No. This has a mutually exclusive list of answers and only one possible outcome.

There are ways to make the markets more granular by creating buckets, but this is more of an art than a science and has possible side-effects. For instance, you could ask the question “What will the exchange rate be between the US Dollar and the British Pound be in 6 months?”, then create buckets “0.0 – 0.25”, “0.26 – 0.5”, “0.51 – 0.75” … “2.0 or more”. The problem is that you might have too many or two few buckets and the data you get back isn’t interesting. Also, the last bucket of “2.0 or more” is much larger than the other buckets in 0.25 increments and therefore has a higher probability by default.

Finally, the market has to be interesting enough to attract a large set of diverse customers to buy and sell the shares. Some thing too niche and the participants share the same level (or lack of) insider knowledge and the results might be skewed.

Once all the criteria for a market is met, it can open for trading. During the market’s run there needs to be away to encourage trades. When dealing with real money, people are encouraged to trade to make more money. Although this might not be as effective a motivating factor as you think. In the US, it is illegal to gamble on sporting events such as the superbowl. So many companies run a prediction market using credits or other non-monetary units. In Ireland and other countries, there is no ban on sports gambling so people use hard-earned money. The results suggest that there is no significant difference in the outcome of a prediction market if it’s based with real money versus play money. Simply having a leader board might be enough of an ego trip for people to “trade their way to the top”.

Another way to encourage trading is to supply as much news and gossip as possible and let people make their own decisions about how this will effect the outcome.

Why markets are better than polls

Phone polls don’t scale. For someone to poll 1,000 people, they need to make 1,000 phone calls. With a web-based prediction market, those 1,000 people can interact almost simultaneously. This allows for more data to be collected durning the prediction market’s life-time than the number of calls any polling company could make.

When someone calls you on the phone and asks, “Will you be voting for Resolution 123 this month?”, there are always extenuating circumstances. Maybe your spouse is in the room, so you lie. Maybe you will say anything to get the person off the line. Maybe the sorts of people who are at home during working hours or even have a land-line phone and are willing to talk to telemarketers skew the results. You are answering what you might feel at the current moment, which could change as the deadline looms and might not necessarily represent the zeitgeist of your area.

Prediction markets get around many of these issues by allowing people to be trading at any time of the day and by decoupling your emotional attachment to the answer and adding economic incentives.

It moves from voting with the heart to voting with the wallet.

The better you can guess how your neighbors will vote, the better you can buy and sell shares, whether you politically agree with what you are buying and selling is completely orthogonal to the topic. Due to this, the prices better reflect the reality of the situation. Now one wants to be on a sinking ship when Gallop rings them to ask whom they’re voting for, but I’d happily buy shares of a sinking ship if I was willing to bet there was a potential pay-off.

Winner Takes All

There are several types of prediction markets, but the one that I am most fascinated by is the winner takes all market. This is a market, when closing, only pays out on a single type of share. An excellent example of a winner takes all market place is the Iowa Electronics Market. The IEM is run by the University of Iowa business school and has special dispensation from the US government to trade with real money. Each year they track several political elections, but every four years the winner takes all presidential election market opens.

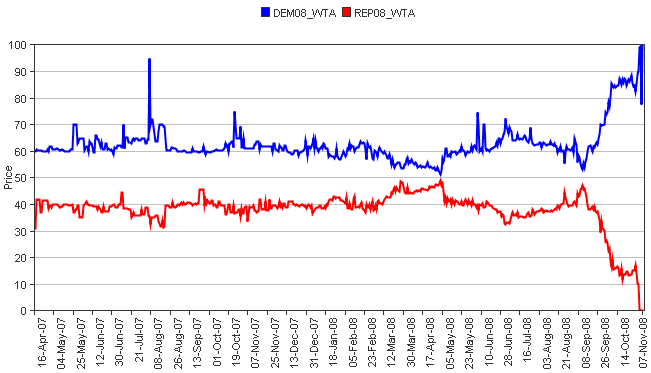

The US Presidential Elections fits nicely into our market requirements; there is a binary YES/NO answer. There is only 1 possible outcome and there is a well defined end date to which an answer can be attached. In 02008, the market ran with shares for both the Democrates (DEM08_WTA) and Republicans (REP08_WTA).

Since the markets had been running for two and a half years prior, they couldn’t connect it with specific candidates, only the parties. The two lines show the trading levels for each party over time and are fixed between $0 and $100. This is important and is where a winner takes all market deviates from markets that you might be used too. In this example, the DEM08_WTA shares were the ones that paid out in 02008. If you had say, 100 shares of DEM08_WTA and 50 shares of REP08_WTA you would only be compensated for the 100 shares of DEM08_WTA at $100 each. The 50 shares of REP08_WTA would be worth zero. The upside is that if DEM08_WTA was trading at a price of $98 when you bought it, when they won you were paid out at $100, a $2 profit. The winner of the market takes 100% of the money. This is where it gets very interesting, because the prices are fixed to sum to $100. Everytime DEM08_WTA went-up it forced REP08_WTA to go down. Why? Because the two shares are mutually exclusive. Only one of the two candidates could win the position of presidency and the kicker is that the prices of the shares directly represent the probability of that outcome. As one share increases in price closer to $100 so does the probability of that occurring. Because the WTA pays out for only the winner, you need a level of confidence in that share to purchase it. You are risking losing everything if it doesn’t win so as the price increases so does your willingness to risk or certainty of its outcome. As one probability goes-up it must force the other down so that the sum of all the possible outcomes equals 100%.

As it got closer and closer to election day the DEM08_WTA shares approached $100. This was not the margin at which they would win, but rather the probability that they would. If the shares were trading at $80/$20 that doesn’t mean it would be a landslide victory at 80%, the ballots could be 54% to 46% but the certainty that it would happen is 80%. This is a point of confusion, the WTA prediction market does not predict the spread, just the winner.

Internal Markets

There are several companies that have used prediction markets internally to help tap the knowledge of their employees. Hewlett Packard used an internal prediction market with a small number staff over 3 years to better estimate printer sales and other aspects of daily operations. Kay-Yut Chen and Charles R. Plott wrote a paper about the experiment entitled Information Aggregation Mechanisms: Concept, Design and Implementation for a Sales Forecasting Problem (PDF). The results from the experiment showed that in almost every case the prediction market outperformed the official HP estimation. That doesn’t mean that the prediction markets were always correct, just better than the official prediction by a small staff of experts.

Google has used prediction markets internally to “forecast product launch dates, new office openings, and many other things of strategic importance to Google”

. They are melding the wisdom of all the employees to get feedback about products and the internal culture.

I think this is an interesting tool for estimating product launch dates. If your boss individually asks you if the product is going to be late you might lie to let him hear what he wants or because you don’t want it to seem like your portion is holding-up the entire launch. Conversely, you can always blame another group saying “testing won’t finish on time” so why should I work hard to complete my tasks on time? In a company of any-size people eat lunch together, have coffee together and are chatting in the halls, via email, IM and other sources. Information is always being exchanged, but it is not quantifiable or collected into a single place. A prediction market allows for some of this information to be converted into a probability through the sale of shares. If the product launch is 6 months out and your team is trading shares of “Will be late” at 80 credits (80% probability it will be late) then you know your team doesn’t have confidence in shipping on time. As a manager you could reduce the feature set to help make the deadline, push back the deadline, or better yet instill confidence and pride in the team and push forward and see if the price of the shares trends the other direction. Prediction markets can easily be anonymous, so even though one team will be finished on time, members of that team might know something across departments that the upper management doesn’t and that knowledge would be reflected in the over all price of the shares. Employees might be confident and truthfully tell their boss they will complete their features on time, but know the another teams are way behind and therefore still trades shares of “Will be late” at a high price (high probability).

Other large companies have experimented with internal prediction markets with mixed success. There are plenty of criticisms on the use and panacea of prediction markets. They are just one of many tools to better interpret and plan for a given outcome, but it does create an opportunity for inclusion in a company because in this case everyone’s opinion really does matter.

Online prediction markets

There are several companies running prediction markets online. Some are for fun, some for money. The Hollywood Stock Exchange (HSX.com) has been trading shares of unreleased movies. This is exciting because their estimates of box-office opening revenues have traditionally out-predicted those of the experts. I image when you ask thousands of people, “Do you think your neighbor would see this movie?”, you’d get a much better feel for the real attendance levels then estimating based on other factors.

The BBC even got into the game with celebdaq and sportdaq which you can trade shares of celebrities and sports stars. Their share values are based on daily news reports and paid out weekly. As people heat-up in the news you stand to gain. Your knowledge of fickle pop-culture allows you to sell when they are at their peak before we see them years later on “Where are they now” style TV shows.

Then there are plenty of sites that have running markets or allow you to set-up your own. Hubdub.com and Predictify are trading shares of news and events and are open for anyone to join in. The Industry Standard works the same way, but is focused on the tech industry getting more in-depth and esoteric than the general markets. If you want to run your own markets inkling is a platform which is open for companies to test the waters. There are plenty more alternatives arriving as everyone is becoming an arm-chair economist.

Prediction markets are a fascinating space combining economics, gaming, politics, sports and other disciplines. I’m very interested and have been pushing for various personal and professional projects where prediction markets offer an answer. I’m excited to see it mature and be an accepted form of information gathering.