Deb Chachra is a Professor of Engineering and one of the early faculty at Olin College, which was founded to rethink engineering education at the undergraduate level. She has research and teaching interests in education, design, and infrastructure, with a background in materials science. She received her PhD from the University of Toronto and held a postdoctoral fellowship at MIT, and her research has primarily focused on biological materials, including heart valves, bone, and the fibre-reinforced polyester made by bees. At this conference, her goal is to help participants develop a deeper understanding of some of the central ideas of materials science, including how they manifest in emerging technologies like 3D printing and bionanotechnology.

WIRED magazine described her work as being plugged Oculus-style into her brain while she meditates on science and culture.

Because…

Since this whole conference is based around the idea of exploring the Web as a Material, it was finally time to get someone who was a proper material scientist to come and explain things to us.

Debbie did not disappoint. With several hands-on excersizes, we were all treated to material science in action.

As she discusses in her session, it isn’t just the material, its the process that’s critical. She talks about a Katana blade and how at the molecular level, the way the atoms are bonded depends specifically in the process and the working of the material. If you had a sub-micro level 3D printer, you could never replicate that sword because the processes of forging and 3D printing are so very different, even though the material might be identical.

In our digital world, we want to have that conversation of what material properties that Web might have, but now we also need to start to consider the process of creation even more importantly‽

Process ➞ Web

In general, we are good at identifying different types of materials. When we see a product, we do pretty well in figuring out what it is made of and its physical properties. This shouldn’t surprise you, because in our day-to-day lives, we are always in touch with materials. Unless we live in some sort of sensory deprivation tank, we all get dressed, use basic tools and interact with the world. All this practice handling products has lead to a deep understanding about how materials function.

At the other end of the spectrum, our model of the material world is a very dumbed down and simplified one. When we interact with a handful of dirt, we’re not thinking about it at the tiny, vast molecular level. We treat all those atoms as a single lump of dirt.

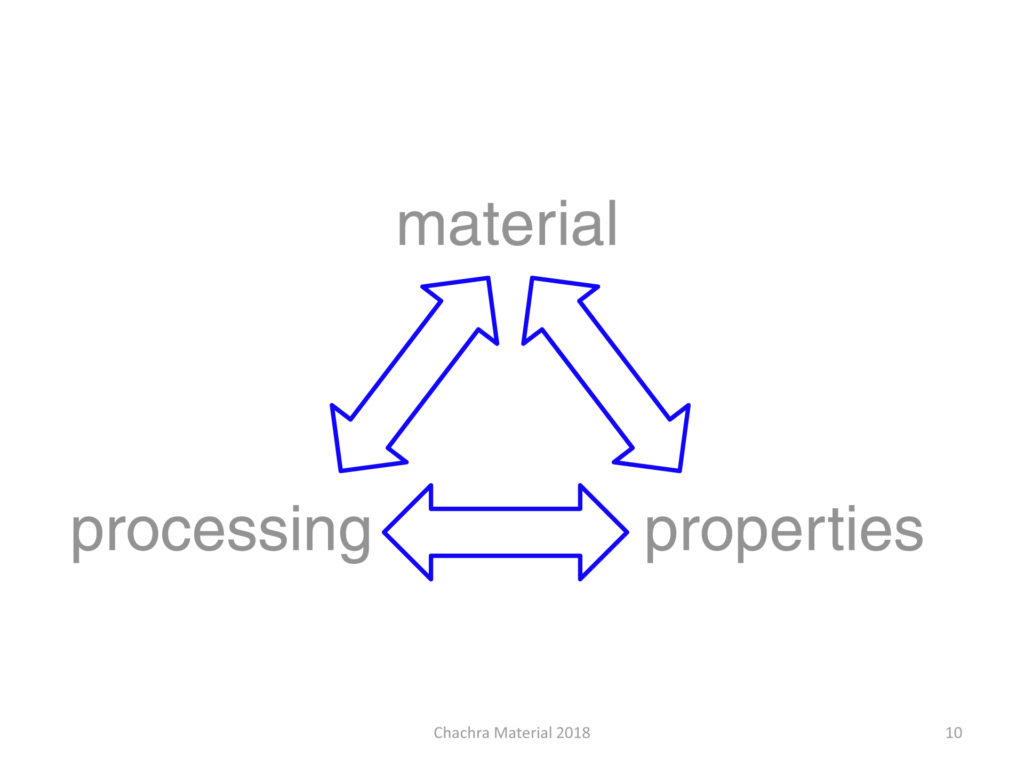

Our lack of understanding arrises in the space between the product and the material. Specifically in two major areas, the processing and the structure.

Processing

How did we get from the raw materials into that shape and function? Something was mined, extracted and then one or more processes took place to convert it into the shape for the final product.

How the processing is done greatly affects the potential outcomes. Working a material too little or too much changes it’s properties and the outcome. The process really maters!

This is illustrated in the making bread process. The ingredients list is very short, but there is a specific process that needs to be followed. If you kneed the dough too much or too little, it won’t create the right amount of glutens. The proofing and rising stages are also key to the process of making bread.

Having all the ingredients and raw materials is not a guarantee of success.

Another example is Spider silk goat milk. Scientists have managed to get goats to produce spider silk protein in their milk. While we know the chemical make-up of spider silk, it is the process that is important into turning that into a silk thread. The spider’s spinnerets doing the processing of the liquid silk protein is the process that makes it special. That processing is not possible in a goat.

Structure

Between the atom and the product, there is a lot of micro and macro structures which we don’t know about.

If you take a paperclip and bend it a few times at the same spot a few interesting things occur at the structural level. The bending is a process that is physically changing the metal. You make it harder by bending it back and forth arganging the atoms, but you are also making it more brittle and easier to break.

If all we knows is the material type, but don’t understand the structure, we can get vastly different outcomes.

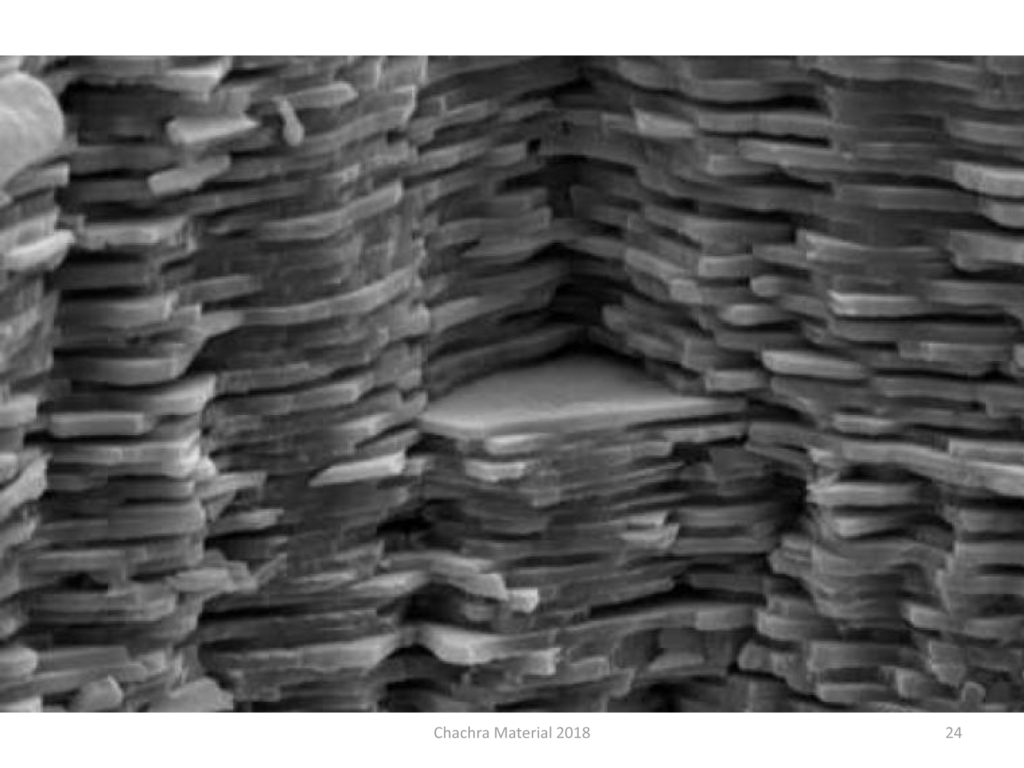

Nacre, or mother-of-perl, is 99% calcium carbonate. That’s chalk or limestone. But the nacre in seashells have very different physical properties from chalk. That’s because in-between these limestone plates is a layer of protein. This subtle structural change has a major difference in how strong and flexible the material becomes.

Material is the infrastructure of design. Affordances of the material is what makes design possible.

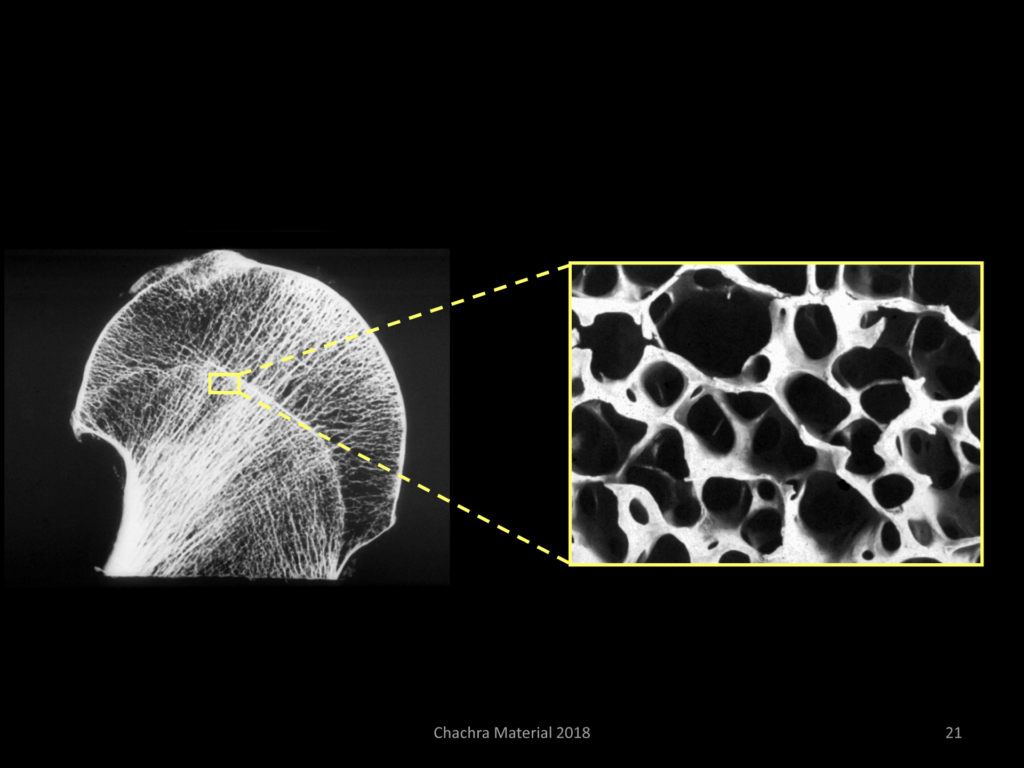

Algorithmically generated biological design is a new and exciting field we all need to be aware of. This is when we let computer algorithms generate structures to maximise and minimise different parameters. For instance, a load bearing connector designed by a human versus one designed by an algorithm trained in biological design to maximise strength while minimising weight and material.

Mother nature has experimented and optimised for a long time, so why not take a queue from her book and use what works.

For instance, bone is a flexible medium that under load, produces more structure, but when it isn’t needed it goes away. There is bone fatigue in astronauts, because they are not putting any weight onto their skeleton, therefore the body doesn’t exert the energy maintaining what isn’t used or needed.

When you look at bone under a microscope, you can see that it is lined-up to support maximal stress. Algorithmic design creates very similar structures.

The last piece of the puzzle that we are missing, in our attempt to better process materials, are the conditions. Now we understand that a product of a material is really a product of the processing of that material. We know that different processing creates different outcomes from the same material. All of our examples in the lab using 3D printing are hot, energy intensive and environmentally sensitive. Nature on the other hand, is creating nacre, silk and even plastics at room-temperature, in salt-water, in a low-energy environment.

We have a long way to go in understanding the material to its fullest if we are ignorant of these processes.

You can view all the video recordings and subscribe to the Material podcast on the Material Archive site.